Summer bees and splits

Read on if you are interested in some details on how our honeybee colonies fared this season.

With beekeeping, there is always a bit of a cycle – ups and downs, good years, and not-so-good years. If I compare this season to the last 3 years where we have been selling honey, it has been more of a down year. But Lord willing, it is not ending that way (more on that later). In the spring, we began with 6 overwintered colonies and 9 new package colonies. I’m including my folks’ colonies in those numbers since they are managed together. Several of the overwintered colonies were weak or lost their queen early on and I merged 4 into 2. One of those two was on my great, great aunt’s property and though we tried several times to help it out with an infusion of bees or brood, it did not remain queen right and could not be salvaged. However, it was an enjoyable time to have the hive on her property for the year or so it was there.

97-year-old Arlene Wilson kept daily tabs on our Russian colony of bees. She is our children’s great-great-great aunt.

The other hive that we combined in the spring did well and became one of the two strongest colonies in Iowa, yielding 4 supers of honey.

Of the other two overwintered colonies that continued on their own, one in MN did great in May filling one and a half supers on a spring nectar flow and then it decided to swarm, leaving a small colony behind that remained weak for the rest of the season. But it looks like it has built up to normal strength in the fall. The other overwintered colony in Iowa was the aggressive one that killed the mouse during the winter. They ended up re-queening and possibly swarming. They are a gentler colony now, but only made one super of honey by the time we harvested.

Of the 9 nine package colonies, my dad’s was queen-less a few weeks later. We re-queened and it has continued OK, but the new queen was never a strong layer, and they produced less than a super of honey by the time we harvested in early August. However, it filled another whole super by the end of August, had a low mite count and generally looked nice going into fall.

Another colony also went queenless right away in the spring. We tried to re-queen, but she didn’t take. They developed laying workers that started producing a lot of drone brood. The colony had to be disassembled and the bees shook out in front of other hives on May 28. Three other colonies developed a brood sickness in June that left melting brown larvae and off-looking white larvae that would develop black spots and die. Had symptoms of European Foul Brood (EFB) and sacbrood. I decided not to spend more money on queens this year, so just monitored the colonies. One did not recover and the remaining very small cluster was shook out on July 7. The second did not recover either, though we allowed it to hang on longer before we found it either absconded or collapsed in early Sept. The 3rd sick hive did recover and ended up producing two supers of honey, which was a pleasant piece of good news.

Frame of sick brood: The pattern is not healthy. The capped cells are not uniform, There are partially uncapped cells, there is dead larvae, and dried out “banana-ed” larvae visible.

Practical lessons:

- Don’t wait too long to intervene in a sick colony. Their genetics may be too “poor” to recover well.

- Spending money on a new queen may be warranted. You can let them raise their own, but they would never produce honey for the season and its still a gamble keeping half the genetics.

- Raising your own queens is ideal, but its difficult to have any available early in the season.

- It may be detrimental to start package colonies on frames from old deadouts of previous season’s sick colonies.

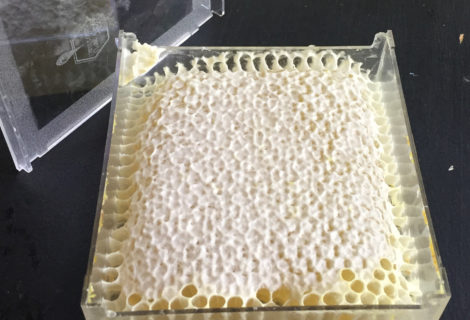

The other 4 package colonies ended up doing well. One was in Iowa and we harvested 4 supers from it. The other 3 were on our MN property and they all fared well, producing between 2 and 4 honey supers a piece, plus a comb honey super. So that means we got honey from 9 of 15 potential spring colonies, each averaging less than 2.5 supers per colony, or roughly 85 lbs per colony. And at the time we harvested the honey, we had at most 10 intact colonies. However, the up side is that the 22 or 23 supers of honey we harvested is comparable to our 2016 season, tying for the second best year we’ve had – mostly due to running more colonies than in 2016.

So let’s compare with last year. In 2017, we also started out with 15 colonies. But not a one of them collapsed that year. Not until January of this year did winter losses set in. 12 of the 15 produced honey for a total of 31 supers, including a second harvest in September (6 supers). There are different ways to look at the numbers. Last year was a record year, but we had more production colonies and they only totaled two more supers than this year for the first harvest. Last year the basswood flow was minimal, but other nectar sources made up the difference. This year, we had a wet spring, and a slow start, the the summer flowering and basswood flow was really good. One of these years we will hit the “sweet spot” where we have strong colonies doing healthy spring build-up along with an awesome summer nectar flow.

Summer Splits and Fall acquisitions

What about a 2nd harvest possibility this year? That’s not going to happen. Looking at the lower colony numbers and weak colonies that we have, I decided to sacrifice any fall harvest we might have gotten and instead focus the colony resources on producing more colonies. Remember, the colony is the “animal” we are dealing with here, not individual bees. How do you reproduce colonies? One way is to just cut them in half. We do this in the spring when we have strong over-wintered colonies (just didn’t happen this year). But another time to do it is in the summer – in the hope that the smaller colonies you produce will build up enough to have a fighting chance to make it through the winter. You take colonies out of production and divide the frames into separate hive stacks.

So on July 28, I started a procedure that I’d never done later in the season like this. I harvested the extra honey supers from the 3 colonies in our woods (leaving some honey for the bees) and proceeded to split each of the 3 colonies so that I ended up with 6 from the original 3. What you do is move the boxes containing the queen to a new location (several hundred yards on the other side of our property in our case) and leave the boxes without a queen in the old location. This means the foragers who are out flying will return to the hive without the queen. I did not introduce new queens at first as I wanted them to raise their own. It is considered late in the season to try something like that, but I like to experiment and that gives me a better feel on timing and scheduling for next year.

One of the split hives with the old queen that was moved to the center of our yard, in the middle of our weedy “pollinator quadrants” .

A week later, my dad and I did the same procedure on two of the hives in Iowa. In September I acquired the two hives of the widow we helped spin out the honey for. These hives had not been managed since early spring except for boxes being added. So it was a risk and adventure moving them onto our property in MN, and that experiment continues. I plan on doing a follow-up post that provides some details on how the splits and acquisitions fared before heading into winter. The upshot though, is that we now have 16 colonies running, which is more than what we started with in the spring. 9 of those is on our MN property, where I never ran more than 3 colonies prior to this year. Every time I walk out into the yard, I have bees following me around, begging for food or exploring some nook and cranny. It’s an interesting situation trying to provide them with sugar syrup for winter stores, as they will consume 30 lbs of sugar a day if I give it to them.

This is not a false-color image. You are looking at bees on the bottom board of a hive that have been dusted with powdered sugar during a mite check. Above those, foragers are flying into the hive, loaded with goldenrod pollen.

Not 20 feet from one of our hives, a colony of bald-faced hornets set up shop and created this large nest. They are part of the food chain here, but since they are such a nasty monarch caterpillar predator and a nuisance to anyone walking by, they had to be dealt with.

Recent Comments